Can we catch the uncatchable? An attempt to capture Turkish Lira's hyper volatility!

Saying that the Turkish lira experienced high volatility during the last decade would be an understatement. We can see why this is true if we compare a simple variance measure, i.e., the annualized standard deviation of the lira, with other major currencies. From 2011 onwards, the lira’s sd stands at 17.2% compared to the Australian dollar’s 10.4%, Swiss franc’s 10.3%, Japanese yen’s 9.04%, Euro’s 8.5%, and Canadian dollar’s 7.5%.

Note: The code used to generate this graph is available at my GitHub repository

Like many other financial assets, we can analyze the lira’s behavior through chartist’s or fundamentalist’s lenses. While covering such two broad perspectives in this short blog is quite challenging, I will summarize the overall situation via these two schools of thought.1 Fundamentalists view the expected changes in economic variables to forecast asset prices. As for the exchange rate, probably the most critical variable is the short-term interest rate. Interest rates are a natural choice as a policy instrument to offset the financial uncertainty encompassing the currency. And like other central banks, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT) used it to control the free fall. Take the one-week repo rate between 2016 and 2018 as an example. It increased from 8% to 16.5% (850 bps) at the beginning of 2018 and eventually reached 24% by September 2018, following a 40% depreciation of the lira in mid-August. However, it got gradually reduced in the subsequent announcements. The lira kept receiving shocks, the worst of which came after the global pandemic. On the 20^{th} of December 2021, the nominal value against USD reached an all-time high of 18.4, decreasing to a closing value of 13.5 the next day. The government announced a scheme on the same day to curb the effects of dollarization. It aimed to protect the lira deposits in the banks against fluctuations in foreign exchange markets. In the past, CBRT also used instruments like reserve option mechanism (ROM), required reserve ratio (RRR), and interest rate corridor (IRO), which were only partially successful. While it goes without saying that the central bank’s policy tools are just a part of the larger picture, noted here is that simply the increase or decrease of the repo rates and reserve requirements won’t control the shocks that may stem from supply and demand or other sources. Domestic and overseas capital movements, geopolitical uncertainty, or even economic uncertainty play their respective roles too. In a recent research (I did as part of my Ph.D. program), some of my results suggested that economic policy uncertainty influenced volatility, especially long-run variance.

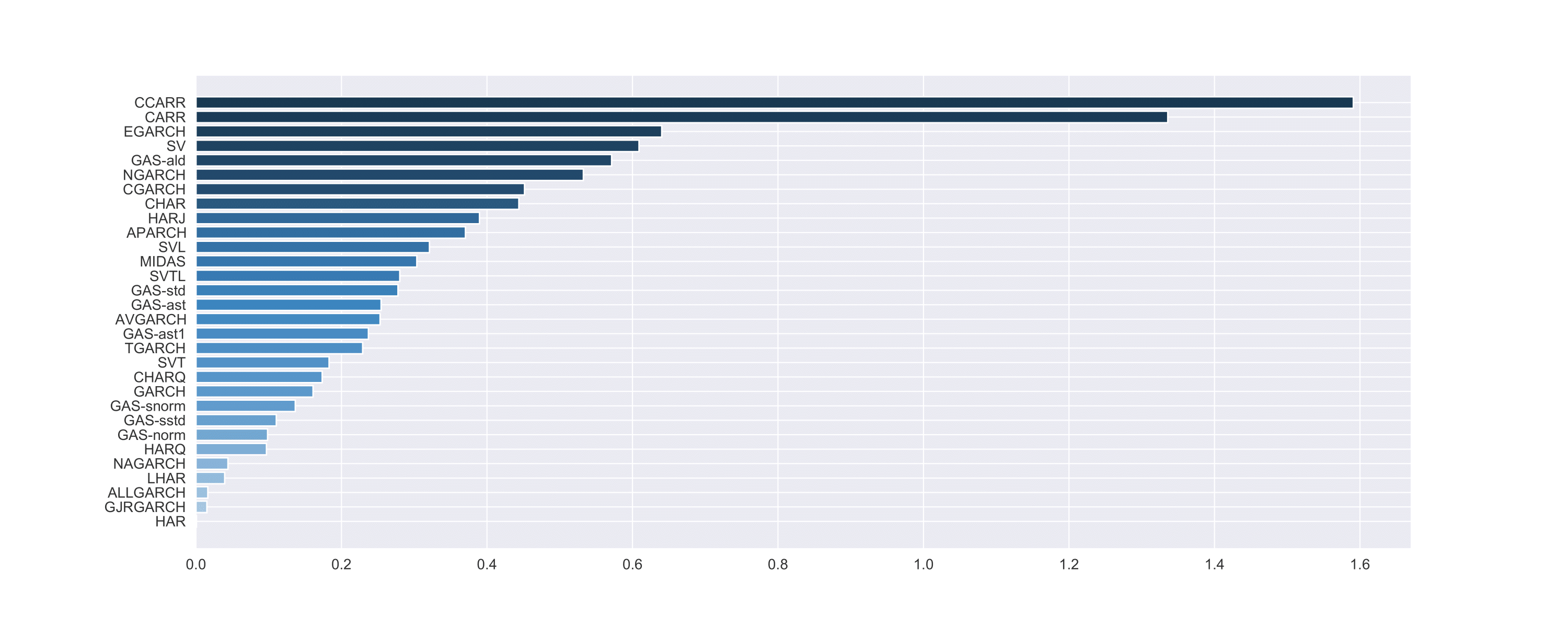

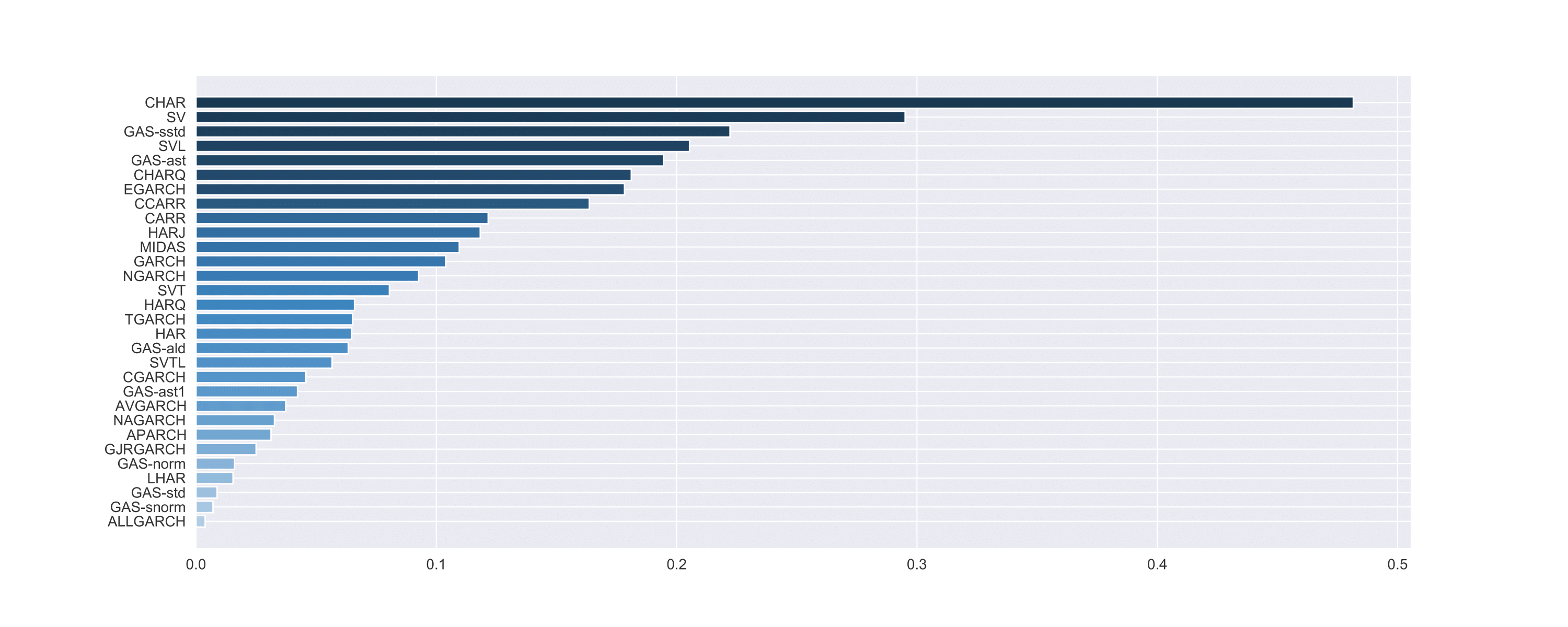

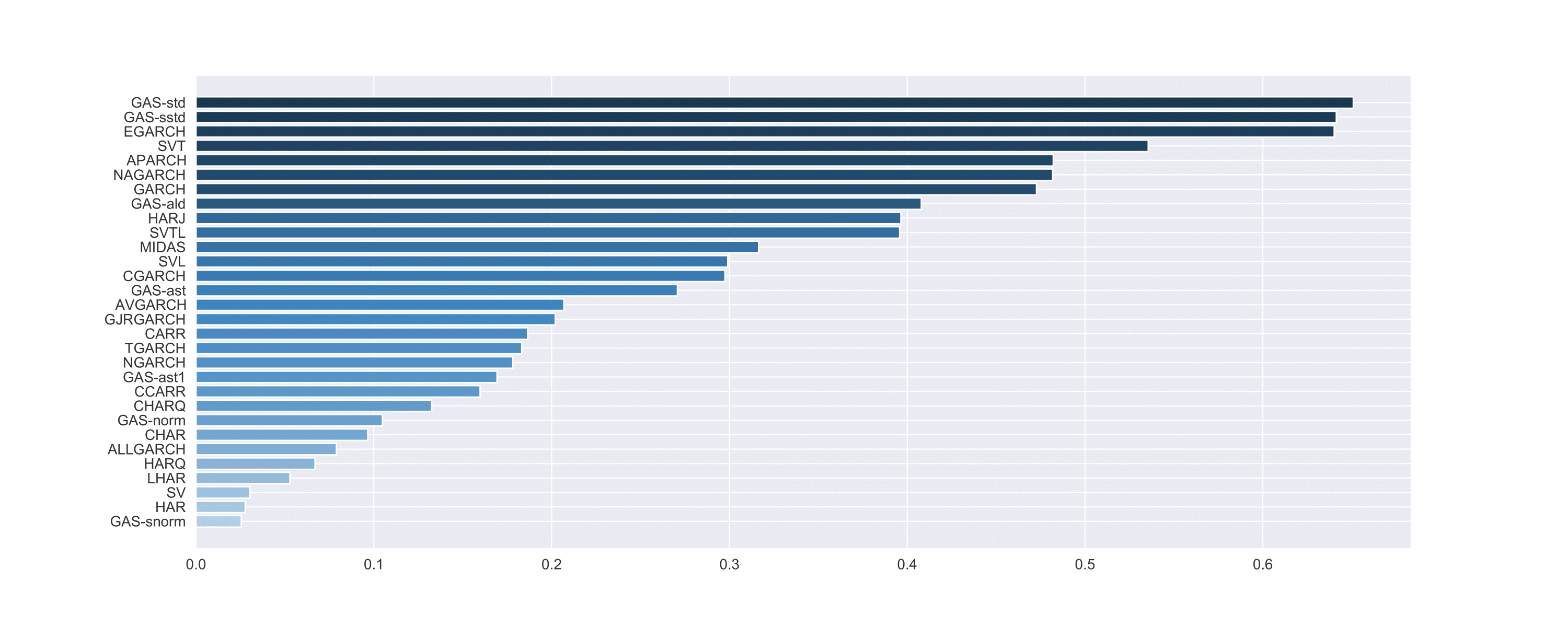

In the same paper, we modeled the Turkish lira’s volatility with seven different groups of statistical approaches, having 76 specifications. Most of the models used estimated volatility with univariate model classes. This idea brings us to the chartist point of view, which states that an asset’s price movements may have an explanation in its history. Our findings were intriguing from several perspectives. Firstly, we observed that to model the lira’s volatility, model specifications with non-gaussian error distributions; provided comparatively decent results. Secondly, it isn’t always necessary to have over complicated techniques to model a currency like a lira. For example, many simple specifications gave better estimates than fancy models; that had jump components in them. In the final part of our study, we applied a support vector regression (SVR) to our variables. We did so to check the effectiveness of an estimate. We showed that this effect depends highly on the proxy used as a dependent variable. For example, when we use the range return (RR) of Parkinson’s as a proxy, estimates from range-based models were better able to explain the variation. We share a part of our analysis in the bar graphs below to provide a brief idea regarding our findings. We used three proxies as dependent volatility measures; these are RR, realized volatility (RV), and moving average squared returns (MASR), given in Figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Disclaimer: Some of the points highlighted in this blog are a part of the second chapter of my Ph.D. dissertation and a paper I have co-authored with my supervisor Prof. Dr. Murat Donduran, of Yildiz Technical University. The code and data used in our paper are also available in a GitHub repository.

-

In a future blog, I intend to cover the main theoretical and empirical models of the exchange rates and hopefully provide a map that provides a systematic picture of the information derived from the literature. It is such an interesting and important issue; that I feel deserves a separate effort! ↩